Mississippi story

My husband’s childhood on an interracial farm led to a lifetime of social justice work.

A defining theme of the third age is reflection on events that have shaped our lives. For Bill Minter, my husband, a seminal experience was growing up on an interracial cooperative farm in Mississippi and the farm’s downfall at the hands of white racists in the Jim Crow South.

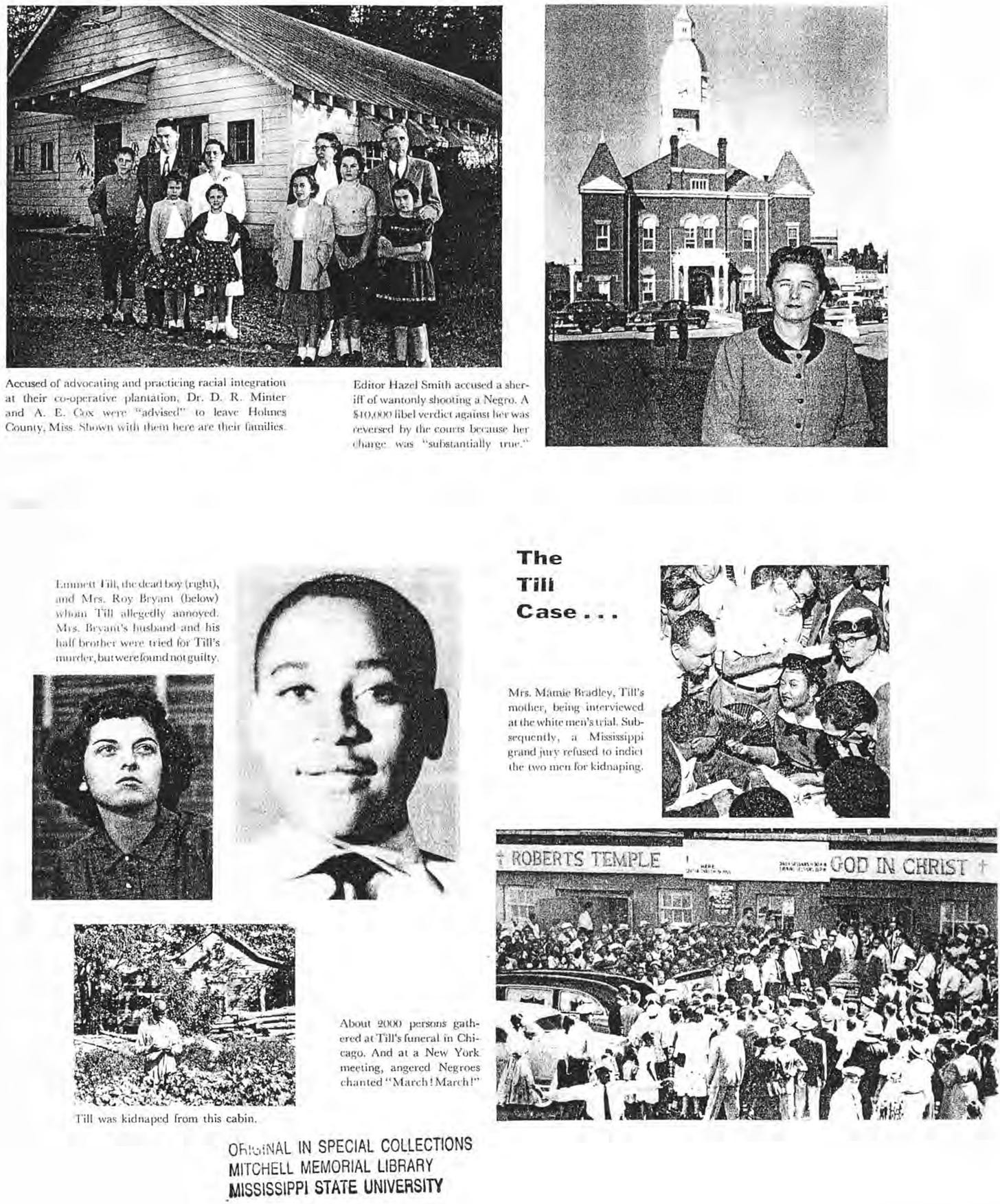

Delta Cooperative Farm was founded in Bolivar County, Mississippi, in 1936. It was backed by Northern philanthropists with ties to Christian socialism and an interest in cooperative models in other countries. Many of the Black and white sharecroppers who moved to Delta had been evicted from plantations across the river in Arkansas and were involved with the Southern Tenant Farmers Union. Among the farm’s white residents were two professional families, the Minters and Coxes.

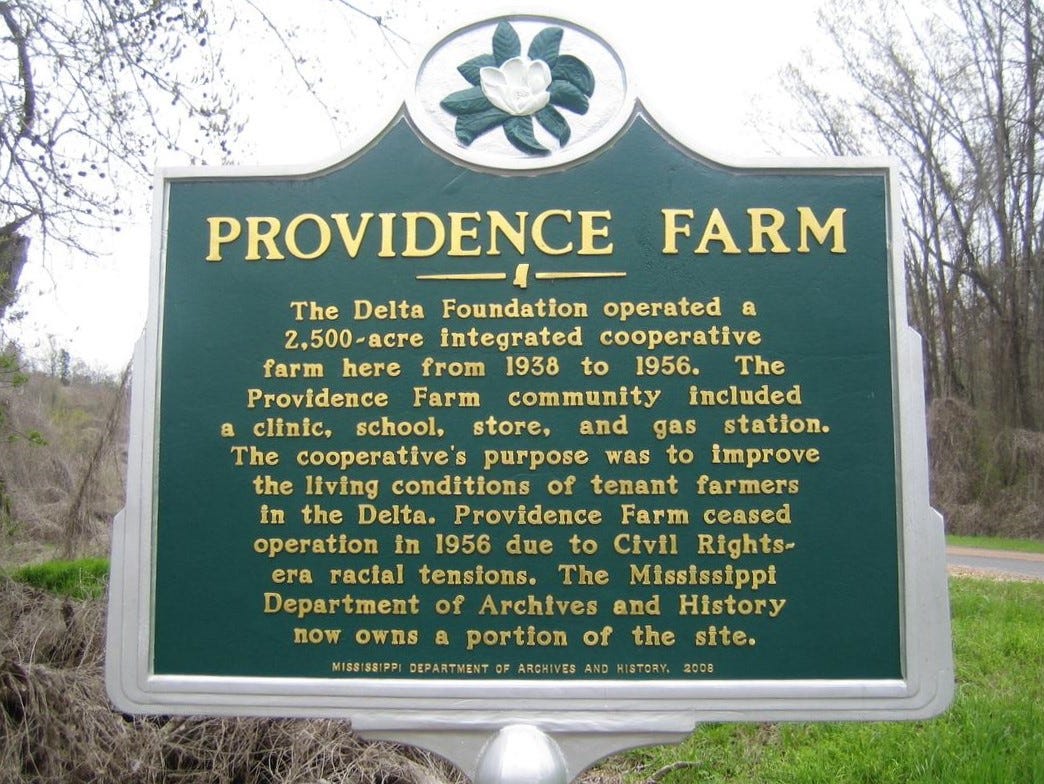

Poor soil, floods and droughts, and faltering management eventually ended operations at Delta. Its successor, Providence Cooperative Farm, started in nearby Holmes County in 1938. Providence was a smaller venture, as many of the Delta sharecroppers left Mississippi during and after World War II.

After serving as a malaria control officer in the Pacific during the war, Dr. David Minter returned to Providence Farm with his family in 1946. With the help of Lindsey Cox, a nurse, Dr. Minter ran the farm’s medical clinic, which served residents of the surrounding area. The farm had a co-op store and credit union that were managed by Gene Cox and Fannye Booker, a local Black schoolteacher who also held classes on the farm for Black children and youth.

By the mid-1950s, backlash to national civil rights pressure was surging in Mississippi and throughout the South. In September 1955 the local White Citizens Council summoned Dave Minter and Gene Cox to a community meeting, where some 500 whites angrily accused the two men of being communists and preaching racial equality. They voted, almost unanimously, that the Cox and Minter families should leave Holmes County.

Waiting at home for Minter to return were his wife Sue and their three children, including Bill, then age 13. I asked him how growing up on Providence Farm and bearing witness to its end shaped the values he holds and the choices he has made throughout his life.

CATHY: What are your early memories of Providence Farm?

BILL: The farm was on the edge of the Mississippi delta, up in the hills. To get to Tchula, the nearest town, it was six miles of dirt road, and then you turned left onto the highway for two miles. The school bus came out to get us. Six to 10 of us white kids on the farm went to the white school in town. It was segregated, as all Mississippi schools were then. When the road was flooded a portion of it became impassable by car. So we’d be driven up to the flooded part, and we would wade or be carried across to meet the bus.

The Providence land was no good for cotton. The farm had a few cattle, a few small fields of corn or vegetables, but not real farming. It consisted mainly of a medical clinic, run by my father, along with a co-op store and a credit union. It was an intentional social justice–type community, supported by liberal philanthropists in the North, including Sherwood Eddy and Reinhold Niebuhr. It wasn’t a self-sustaining operation.

My father treated both Blacks and whites. Local mythology is that there was no segregation at the clinic, but as a matter of fact there were two waiting rooms. They were not marked as white and Black, but by custom, most of the white patients sat in one and most of the Black patients sat in the other. However, the one for white patients, who were far less numerous, was smaller and not air-conditioned, and it was the larger one for Black patients that was air-conditioned at one point.

CATHY: What kinds of medical problems did your father treat?

BILL: Pretty much everything, but two very common things were malaria and venereal diseases. I still have his handwritten clinical journal, showing each patient’s name, the diagnosis, and the charge, paid or not paid. The charges were 50 cents or something.

A team of nurses from Alpha Kappa Alpha, the country’s oldest Black sorority, which Kamala Harris later belonged to, volunteered in Holmes County every summer for many years. They also donated equipment, including an x-ray machine. When I returned to the site of Providence Farm in 1987, I found the machine abandoned and rusted in the old clinic, which was still standing although not in use.

CATHY: As a child, were you aware of racial segregation and tensions in Holmes County?

BILL: It was obvious that we went to separate schools, and as young children we took for granted the racial separation in the schools and town. The cooperative was a different world. Black and white families ran the farm together, and my sisters, particularly, remember playing with the farm’s Black children. My parents insisted that one should treat everyone with respect, regardless of race, calling all adults Mr. So‑and‑So, Mrs. So‑and‑So. I became aware of racial tension in the county only in the mid-1950s, when I was around 12 years old. My sisters, four and five years younger than me, were not aware of it at all.

During the school year of 1954–55, I was sent to boarding school in Tucson, Arizona. My asthma was one of the reasons, but I now suspect that it was also because of the increasing tension. However, I came back and spent my freshman year at the segregated high school in Tchula. One of my classmates was the son of the local sheriff, whom my father had testified against in court. The sheriff had shot a Black man in the leg and my father had treated the wound. That was one of the incidents that brought hostility against Providence Farm into the open.

CATHY: Brown v. Board of Education, the 1954 desegregation ruling, didn’t have any impact on your schooling?

BILL: No, no. It was not implemented either there or elsewhere in the South for many years. What it did was to ignite the organized resistance of white racists. The White Citizens Council was a supposedly “respectable” version of the Ku Klux Klan. Its members included businessmen, bankers, and clergy – “Ku Klux Klan in suits” was the nickname. The chapter in Holmes County was the second in the state, I think. It did in the open what the Klan had historically done wearing sheets.

The white racist reaction was growing throughout 1954 and 1955. It led to the killing of Emmett Till in August 1955. It also led to a less violent attack, but still an attack, on Providence Farm a month later.

CATHY: What were the charges against the farm?

BILL: That Blacks and whites had supposedly swum together in a pond. Actually, both whites and Blacks had swum in that pond, but not at the same time. Basically it was that there was mixing going on between whites and Blacks, and that therefore people on the farm were communist.

The White Citizens Council called a meeting in Tchula and ordered my father and Gene Cox to appear. There were some 500 whites there, and they voted with only two or three dissenters that the people on Providence Farm should get out of Holmes County.

CATHY: But you stayed for some months, right?

BILL: We stayed for almost a year. It was a tense time. Anonymous threats came in by phone and letter. The previous spring, my father had been forced out of his positions as an elder and Sunday School teacher at the Presbyterian church my family attended. After the mass meeting, Blacks who lived as sharecroppers on plantations, or who depended on whites for their employment, were told not to come to Dr. Minter’s clinic. Most of those who continued to come were Black small farmers who had some independent landholdings up in the hill country and didn’t depend on whites for survival. My father had a number of white patients, but almost all of them stopped coming. His clinic also lost part of its insurance, which was canceled by the company.

Finally, the Minters and Coxes decided that they were not helping people by staying, but simply attracting more persecution to them. We moved to Tucson in July 1956 and the Coxes moved to Memphis, Tennessee.

CATHY: How did this experience influence your later life, including your choice to focus on Africa?

BILL: It meant that opposition to white racism was visceral. I wasn’t killed in Mississippi; I didn’t have relatives killed. But I saw racism’s effect and I was outraged by it. Commitment to social justice and antiracism is what motivates my life.

My first time in Africa was on a junior year abroad in Ibadan, Nigeria, organized through the Presbyterian Church. That determined that there would be an Africa connection. Later, in the summer of 1965, I did voter registration with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in southwest Georgia. And in 1966 I returned to Africa with my first wife, Ruth Brandon, to teach at a school run by Frelimo, the Mozambique Liberation Front, first in Tanzania and later inside Mozambique. Since returning to the States in 1976, I’ve continued progressive advocacy on African and global issues, including through my AfricaFocus Notes. My work today builds on the foundation of my family’s experiences in Mississippi more than 70 years ago.

Further reading on the Delta and Providence cooperative farms:

Robert Hunt Ferguson, Remaking the rural South. University of Georgia Press, 2018.

Sam H. Franklin, Jr., Early years of the Delta Cooperative Farm and the Providence Cooperative Farm. 1980.

Fred C. Smith, Cooperative farming in Mississippi. Mississippi Historical Society, 2004.

Hodding Carter, Racial crisis in the Deep South. Saturday Evening Post, December 17, 1955, pp. 26–27, 75–76.

Fascinating perspective on that era - and its roots and branches that still reach to this one . Thanks so much, Bill and Cathy, for sharing this story.

Good to know this history and reflect how it influenced our trajectory. Good to reminded of the violence and challgnges and bviolence the African Americans faced then and that still continues. Amazing effort by Winters and others to support the black community in Mississippi. So many experiences from our past inform the work today..